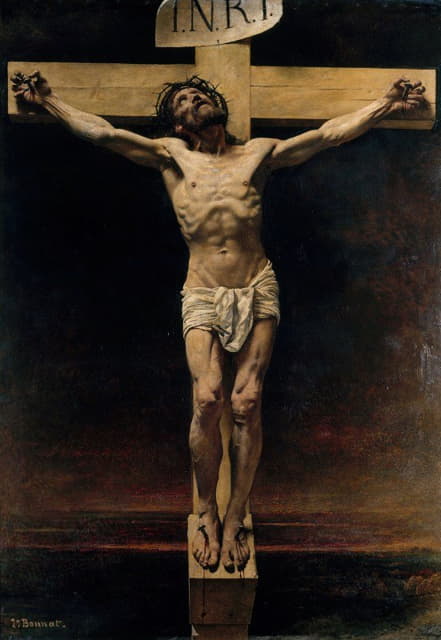

作品名称:Christ on the cross (1846)

艺术家:欧仁·德拉克罗瓦 Eugène Delacroix (法国, 1798-1863)

作品介绍

机器翻译:

德拉克罗瓦描绘了《约翰福音》中描述的一个时刻,即基督在临死前对他的母亲--圣母玛利亚和他的一个门徒--约翰讲话(约翰福音19: 25-30)。基督的母亲穿着独特的蓝色和黄色长袍,倒在马利亚-克利奥法斯和约翰的怀里。在十字架脚下,抹大拉的马利亚一边祈祷,一边仰望着基督。加略人犹大通常不会出现在这样的场景中,但德拉克洛瓦把他放在右下角。犹大现在明白了他背叛基督的后果。左边中距离的两个罗马士兵在观察这个场景。

尽管画布的尺寸相对较小,德拉克洛瓦通过将观众与右下角被压缩在一起的人物置于同一高度,达到了巨大的戏剧性效果,因为我们也在仰望着基督的身体。通过将风景缩减到一个狭窄的带子,德拉克洛瓦进一步强调了他们反应的人类戏剧性。基督身体的青灰色特别引人注目,并被占画面大部分的暴风雨天空的灰色和粉褐色所放大。红色的长袍与基督的伤口流出的血相呼应。在德拉克洛瓦的许多后期作品中,草图和成品画之间的严格区别可能会变得模糊不清。在这幅画中,笔触的激动质量--从薄薄的几缕到厚厚的颜料块--使这幅画具有素描的即时性和使整个画布充满活力的表现力。

在他的一生中,德拉克洛瓦一直在研究和复制旧大师的画作。与这幅画最相关的是鲁本斯的《长矛》(1620年,安特卫普皇家美术博物馆),德拉克洛瓦凭记忆临摹了两次,可能是在他1850年第二次去比利时之后。对鲁本斯的钦佩是德拉克洛瓦对北欧艺术家,包括雅各布-约尔丹斯和伦勃朗的宗教画作的广泛欣赏的一部分。评论家泰奥菲勒-戈蒂埃(Théophile Gautier)也注意到了一个更现代的参考,即皮埃尔-保罗-普鲁东(Pierre-Paul Prud'hon)的《十字架上的基督》(巴黎卢浮宫),该作品曾在1822年的沙龙中展出过。

德拉克罗瓦多次描绘了《圣经》中的故事和事件,但耶稣受难是他经常回到的主题,尤其是在他的晚年。他曾在1835年的沙龙上展出过一幅更大的耶稣受难图,表现的是两个盗贼之间的基督(凡尔纳美术博物馆),并在1847年的沙龙上展出了另一幅耶稣受难图,在这幅画中,基督被放在了更中心的位置(巴尔的摩沃尔特斯艺术博物馆)。19世纪40年代末还创作了几幅油画和粉彩画草图。这个版本的耶稣受难图表明德拉克洛瓦在19世纪50年代仍在探索呈现这一主题的新方法。

评论家和诗人查尔斯-波德莱尔(Charles Baudelaire)是德拉克洛瓦最伟大的支持者和最敏锐的当代观众,他声称德拉克洛瓦创造了真正真实的宗教艺术,因为他的气质和基督教的真实情感之间有亲和力:"也许只有他,在这个不信教的世纪,创造了宗教绘画,既不像一些为竞争而创作的作品那样空洞、冷漠,也不迂腐、神秘、新基督教。 ......他所擅长的真正的悲伤,完全适合我们的宗教,一个深刻的悲伤的宗教。

原文:

Delacroix depicts a moment described in Gospel of John, when Christ addresses his mother, the Virgin Mary, and one of his disciples, John, just before he dies (John 19: 25–30). Christ’s mother, dressed in distinctive blue and yellow robes, collapses into the arms of Mary Cleophas and John. At the foot of the cross, Mary Magdalene prays as she looks up at Christ. Judas Iscariot is not normally shown in such scenes, but Delacroix includes him in the lower right corner. Judas now understands the consequences of his betrayal of Christ. Two Roman soldiers in the mid-distance on the left observe the scene.

Despite the relatively small size of the canvas, Delacroix achieves great dramatic effect by placing the viewer at the same level as the figures compressed together in the lower right-hand corner as we, too, look up at Christ’s body. By reducing the landscape to a narrow band, Delacroix gives further emphasis to the human drama of their reactions. The greenish-grey pallor of Christ’s body is particularly striking and is amplified by the greys and pinkish-browns of the stormy sky that fills most of the picture. The red robes echo the blood flowing from Christ’s wounds. In many of Delacroix’s later paintings, rigid distinctions between a sketch and a finished painting can be blurred. In this picture, the agitated quality of the brushwork – which ranges from thin wisps to thick clots of paint – gives the painting the immediacy of a sketch and an expressive energy that animates the entire canvas.

Throughout his life, Delacroix studied and made copies of Old Master paintings. Most pertinent to this picture was the The Coup de lance by Rubens (1620, Musée Royal des Beaux-Arts, Antwerp) which Delacroix copied twice from memory, possibly following his second trip to Belgium in 1850. This admiration for Rubens was part of Delacroix’s wider appreciation of the often deeply expressive religious paintings of Northern European artists, including Jacob Jordaens and Rembrandt. The critic Théophile Gautier also noted a more contemporary reference, to Christ on the Cross (Louvre, Paris) by Pierre-Paul Prud‘hon, that had been exhibited at the Salon of 1822.

Delacroix depicted stories and incidents from the Bible many times, but the Crucifixion was a subject to which he often returned, especially in his later years. He had previously exhibited a larger version of the Crucifixion, showing Christ between the two thieves (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Vannes), at the Salon of 1835 and had exhibited another Crucifixion at the Salon of 1847 in which a more centrally placed Christ is the primary focus (Walters Art Museum, Baltimore). Several oil and pastel sketches were also produced in the late 1840s. This version of the Crucifixion shows that Delacroix was still exploring new ways of rendering the subject in the 1850s.

The critic and poet Charles Baudelaire, Delacroix’s greatest champion and most perceptive contemporary viewer, claimed that Delacroix created genuinely authentic religious art because of the affinity between his temperament and the true sentiment of Christianity: ’perhaps he alone, in this century of nonbelievers, has created religious paintings that were neither empty nor cold, like some works created for competition, nor pedantic, nor mystical, nor neo-Christian ... the genuine sadness for which he had a flair was perfectly suited to our religion, a profoundly sad religion.'

高清图片下载

图片尺寸:4865 x 6000 像素

图片大小:6.68 MB

图片格式:JPG

图片分辨率:96 dpi

水印情况:无水印

版权信息:公有领域,免费可商用

下载方式:直链下载(非百度网盘)

下载格式:Zip压缩包

部分中文由机器翻译,可能并不准确。